By: Lauren Sepp, UW Graduate Student, Human Centered Design & Engineering

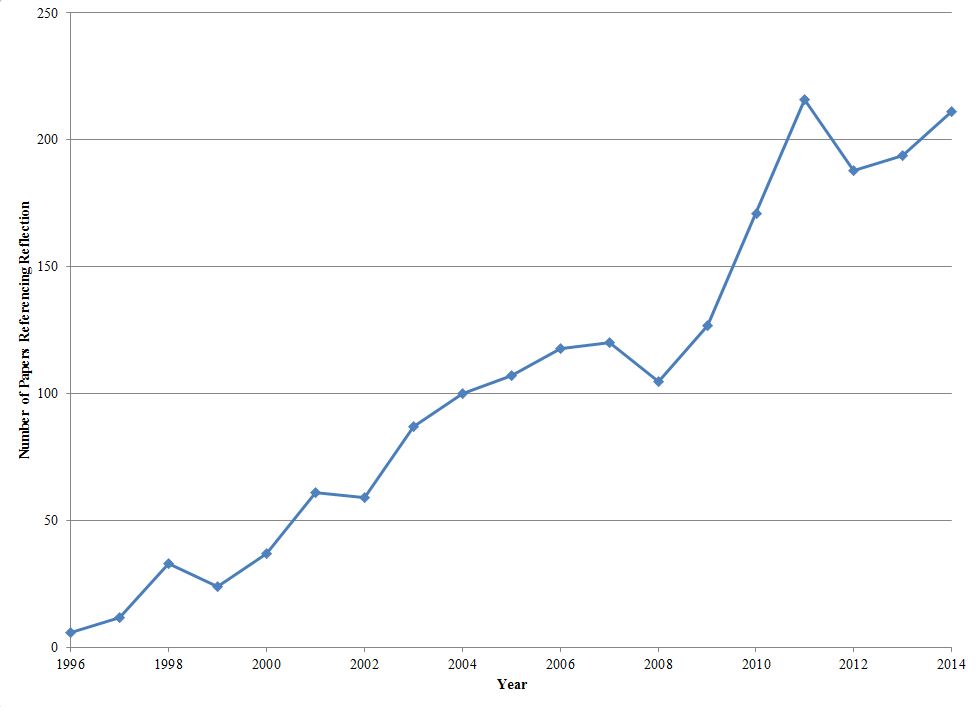

Recently, we performed an investigation into the number explicit references to reflection in the American Society of Engineering Education (ASEE) conference papers. It was found that over the last 14 years of the conference, explicit references to reflection have increased drastically. (Figure 1)

What is even more exciting is that reflection is also getting some attention outside of formal scholarship. A recent blog post by David Gooblar, a literature and writing teacher at Mount Mercy University and Augstana College focuses on how to get students to think about how they think. The main focus of his push is to introduce metacognitive methods to students to take the burden of facilitation and student introspection away from the teacher and empower students with those critical self-reflection skills. David suggests a variety of activities to support metacognitive growth via experiences including exam wrappers, which many of us are familiar with, and another activity called “knowledge ratings.”

Originally from Tamara Rosier, a leader at the consultancy Acorn Leadership, “knowledge ratings” require students to be focused on their understanding of class material while the class is in session. Students are asked to rate their knowledge on a scale of 0-3, with 0 indicating not knowledgeable. By the end of the class, the goal is to have each student recording a score of 3. Mid-way through the class period, the instructor takes a break to evaluate where they are at. The instructor will ask students what gaps they have preventing them from achieving a 3. A discussion ensures and the remainder of the class is focused on closing those knowledge gaps.

David suggests that these metacognitive exercises are trying to “…force students to think about their own learning practices. The goal here is to make students’ behavior visible to themselves, with an eye toward gaining better control over that behavior.”

If metacognition leads to “better learning” as David suggests, how are we facilitating these ideas in our own classrooms? By shifting the intellectual responsibility to the students, can we enable them to become more self-aware, more responsible for their own learning, and better situated for life after college? No doubt, these metacognitive and reflective practices can only help students to achieve the aforementioned qualities.

David concludes by saying, “Too often, we assume that students know enough about themselves that our comments and suggestions will be enough to provoke positive change. But self-awareness and self-reflection (not to mention good study habits) are not skills all students possess. Promoting those skills in class can make our lives as teachers a lot easier.”

So let’s follow his charge and continue to explore what it looks like to facilitate metacognitive and reflective practices in the classroom not only for the sake of the students, but for the sake of the educators too.

Link to blog post: https://chroniclevitae.com/news/959-getting-students-thinking-about-thinking